Gender Studies (CSS): Status of Women in Pakistan 2024

|

| Mera Jism Meri Marzi |

VI. Status of Women in Pakistan

Topics Covered:

▪ Status of Women’s health in Pakistan

▪ Status of Women in Education

▪ Women and Employment

▪ Women and Law

▪ Status of Women’s health in Pakistan (2024)

|

| Status of Women's health in Pakistan |

What is status of women’s health in Pakistan? How it could be improved within the available economic resources?

Health is a

state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being and does not mean the

mere absence of disease or infirmity. The progress and development of nations

are interlinked with the health of women. If the women are healthy, they will

have healthy children and they may be in a position to take care of the entire

family.

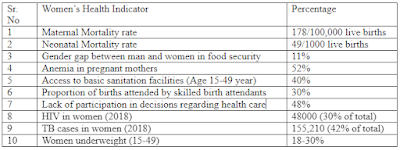

Pakistan, despite many national and international commitments, has failed to uplift the poor health conditions of women. Following indicators shows the actual state of women’s health in Pakistan:

|

| Statistics of women's health issues in Pakistan |

The status of women health can be improved in Pakistan by removing following causes which are behind their poor health:

- The dogmatic and extremely narrow approach to women’s rights and indifference towards women’s health is the main reason why women are not able to get the proper medical attention.

- Hurdles in improving women’s health include low investment in the health sector, rapid population growth.

- Chronic malnutrition among women and, especially girl children, against whom there is cultural and social discrimination in the distribution of household resources.

- Domestic violence remains a chief cause of complications related to pregnancy including unwanted pregnancies, lack of access to family planning services, complications due to frequent and high-risk pregnancies, lack of follow-up care, sexually transmitted infections, and other psychological problems.

- Factors like lack of awareness regarding women’s health requirements, low literacy ratio, low social status and civil constrains on females are responsible for women’s below standard health in Pakistan.

Pakistan was described as “among the world’s worst performing

countries in education,” at the 2015 Oslo Summit on Education and Development.

The new government, elected in July 2018, stated in their manifesto that nearly

22.5 million children are out of school. Girls are particularly affected.

Thirty-two percent of primary school age girls are out of school in Pakistan,

compared to 21 percent of boys. By grade six, 59 percent of girls are out of

school, versus 49 percent of boys. Only 13 percent of girls are still in school

by ninth grade. Both boys and girls are missing out on education in

unacceptable numbers, but girls are worst affected.

Lack of access to education for girls

is part of a broader landscape of gender inequality in Pakistan. The country

has one of Asia’s highest rates of maternal mortality. Violence against women

and girls—including rape, so-called “honor” killings and violence, acid

attacks, domestic violence, forced marriage and child marriage—is a serious

problem, and government responses are inadequate. Pakistani activists estimate

that there are about 1,000 honor killings every year. Twenty-one percent of

females marry as children.

Article 25-A of the Constitution makes

it clear that the government has to provide free education to all children from

the age of five to 16. But many continue to be overlooked by the state.

But, political instability, disproportionate influence on

governance by security forces, repression of civil society and the media,

violent insurgency, and escalating ethnic and religious tensions all poison

Pakistan’s current social landscape. These forces distract from the

government’s obligation to deliver essential services like education—and girls

lose out the most.

There are several reasons for this,

all interconnected. While education and textbooks may be free of cost, there

are other expenses such as admission fees, school bags, uniforms, shoes,

stationery, etc. In households with several children, the added costs

overburden poor families. Private school, even if ‘low cost’, are out of the

question for this group.

The second issue is transport. Schools

are often at a long walking distance, and parents may not be able to afford

rickshaws to pick and drop their children. While, the vast majority of public

schools in Pakistan are at the primary level, secondary schools are at even

greater distances. So even if they complete primary education, they are unable

to study further due to logistical constraints. Linked to the issue of

transport is safety. Parents cannot always accompany children, and when the

girl child hits puberty or begins to ‘look’ mature, she (rightly) fears

harassment and abduction. Tied to these fears are notions of ‘honour’, but

these are often a cover for legitimate security threats or attempts at masking

poverty.

Another reason for losing interest in

education is the presence of apathetic teachers, who may turn a blind eye to

bullying or administer corporal punishment and be guilty of discrimination.

Girls, especially the eldest

daughters, are kept behind to help out with household chores or take care of

younger siblings. Seen as an economic ‘burden’ or just another mouth to feed,

they are then married off and forced to be mothers when they are still children

themselves.

|

| Women Employment in Pakistan (2024) |

Pakistan has held the second-to-last

spot on the Global Gender Gap Index for five years in a row (2012-17). The

index measures countries’ progress towards gender parity on: economic

participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and

political empowerment.

Though women constitute 49% of

Pakistan’s population, they constitute only 24% of the labour force. The ILO

data indicates that Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for men (82.5%) is

more than three times higher than women (24.8%). The gender gap in LFPR is one

of the world’s highest, making Pakistan comparable with Arab states and

countries of North Africa. Even when women want to participate in the labour

force, they are unable to find employment. There is a noticeable gender gap in

the unemployment rate. It is 5% for male workers and 9% for female. In the

urban areas, the female unemployment rate rises to 20% while that of males is

6%.

Women’s share in wage employment is

only 15% as they are engaged mostly as contributing family workers (54%),

eventually working without pay. A UN-Women study estimated the value of female

contributing family workers as nearly 4% of GDP (Rs400 billion in 2014). The

hourly gender wage gap is estimated at 26%, indicating that women’s wages are

only 74% of men’s wages. Only 37% of women workers are paid wages regularly.

Others are engaged as part time or piece-rate workers. Of the regularly paid

women workers, 55% received less than the applicable minimum wage (Rs12,000) in

2014-15.

The Employment-to-Population Ratio

(EPR) is 20% for female workers and 64% for male workers. The EPR represents

the share of unutilised labour in an economy. Pakistan’s current labour

underutilisation rate for women workers is 80%. Even when women have jobs, they

face sectoral or occupational segregation. The Labour Force Survey 2014-15, the

most recent available, indicates that women are concentrated in agriculture

(72%), manufacturing (14%) and community and personal services (11%). In the

case of occupational groups, women are mostly working as skilled agricultural

workers (62%), elementary/unskilled workers (15%) and craft and related trade

workers (13%). Less than 2% of the female labour force is registered with the

provincial social security institutions thus leaving them without any social

protection in the event of workplace accident or disease or maternity.

Most women are engaged in the informal sector, working without any legal protection as domestic workers, home-based workers and piece-rate workers for the manufacturing firms. Though Punjab and Sindh have announced policies for domestic and home-based workers, no enforcing legislation has been enacted so far.

How to solve

women’s low employment issue?

The usually identified factors that promote

(conversely restrict) female labour force participation include educational

attainment, fertility, family size and income, being the head of the household,

religion along with local customs and social norms, and marital status.

Availability of work-family reconciliation measures, including of part-time

work for women (not regulated in Pakistan), fully protected paid

pregnancy-related leaves, availability of childcare subsidies. and statutory

right for the nursing mothers to have breastfeeding breaks have a significantly

positive impact on female labour force participation. The major challenges to

female labour force participation include lack of affordable and accessible

transport and childcare, workplace harassment and discrimination, and work and

family balance.

A much-neglected factor and

consequently a challenge is lack of ‘enabling labour legislation’. Legislation

prohibiting workplace discrimination, including harassment and guaranteeing pay

equality, even when implemented in a lacklustre way, has a symbolic

significance, leads towards an attitudinal change by shaping public attitudes,

allows inspection by labour departments and court action for enforcement.

Pakistan direly needs federal

anti-discrimination framework legislation in line with the core ILO Conventions

and CEDAW. Such legislation should prohibit discrimination on the ground of

sex, age, religion, disability, trade union membership, etc, and ensure equal

pay. The anti-discrimination legislation should also consider issues of violence

and harassment at workplace, and treat these as occupational health and safety

issues.

The ILO suggests that minimum wage

policies can be used to combat gender-based pay discrimination. Minimum wage

legislation and policies can also be used for targeting specific vulnerable

groups of workers, earlier excluded from the purview of minimum wage

legislation, ie, domestic workers, home-based workers and the informal sector

workers.

Legislation should allow for maternity

protection, including 14-week maternity leave (currently 12 weeks) as well as

paternity leave and parental leave. Currently, maternity benefits legislation

places all the burden of income replacement during maternity leave on the

employer unless worker is registered with a social security institution. For

this reason, employers show inhibition in hiring women workers. If maternity

leave is financed through general taxes, employers will increase hiring of

women workers. The tax benefits can also be given to employers who hire female

workers above a certain percentage.

Though laws can help in attitudinal

change, these are not enough to create inclusive and gender equitable labour

markets. Legislative efforts need to be complemented with sufficient budgetary

allocations for departments/institutions tasked with the enforcement of

legislation, vibrant labour inspection system, dissuasive penalties, increased

awareness of workers about their rights, access to enforcement mechanisms and

protections of workers against victimization.

▪ Women and Law

|

| Women and Laws in Pakistan |

Government Initiative for combating the menace of violence against women and important legislations to promote women emancipation

During the last

decade, the government of Pakistan has passed a bundle of new pro- women laws

to protect women against violence and harassment. However, these laws seem to

have done little to change attitudes and practices. Around 27 per cent of women

in Pakistan experience intimate partner or domestic violence in their lifetime

and only 51 per cent perceive themselves to be safe in their communities. Pakistan ranked 164 out of 167 in the Women, Peace and Security Index, 2019,

issued by George Town Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS).

·

The Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention Act, 2011: It made amendments in Pakistan Penal

Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure to punish perpetrators of acid crimes

by clearly including acid crimes in the definition of hurt. The definition of “hurt”

now includes “hurt by dangerous means or substance, including any

corrosive substance or acid to be crimes”. Under section 336-B of

Pakistan Penal code, punishment for offenders can extend up to life

imprisonment, along with a fine, which may not be less than five hundred

thousand rupees.

·

Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act, 2011: The Prevention of Anti-Women

Practices (Criminal Law Amendment) Act 2011 prohibits several oppressive and

discriminatory customs practiced towards women in Pakistan. Customary practices

that are criminalized under this Act include: depriving women from inheriting

property by deceitful or illegal means is punishable with imprisonment of 5 –

10 years, or fine of 1,000,000 rupees, or both. The forced marriages are

punishable with 3 – 10 years imprisonment, along with a fine of 500,000 rupees.

Whereas, forcing, arranging or facilitating a woman’s marriage with the Holy

Quran is punishable with imprisonment of 3 – 7 years, along with fine of

500,000 rupees.

·

Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offense of Rape) Act 2016: Under this law rape,

gang rape, rape of minors and/or persons with disabilities is

punishable with imprisonment for life and fine. Government officials who take

advantage of their official position and commit rape (e.g.

custodial rape) are liable to imprisonment for life and fine. Whoever

prints or publishes the name or any matter which may publicize the identity of

an alleged victim of rape, gang rape, or outraging modesty of a

woman, shall be punished with a maximum of 3 years imprisonment and fine. A

trial for rape shall conclude within three months, failing which the

matter shall be brought to the notice of the Chief Justice of the High Court

for appropriate directions. Public servants (e.g. police) who fail to carry out

investigation properly will be punished with imprisonment of 3 years or fine or

both.

·

Criminal

Law (Amendment) (Offences in the name or pretext of Honour) Act, 2016: According to this law murder

committed in the name of honour is punishable with death or imprisonment for

life even if the accused is pardoned by the Wali or other family members of the

victim, the Court will still punish the accused with imprisonment for life.

·

Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016: In 2016, the National Assembly

enacted the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (“PECA”) to provide a

comprehensive legal framework to define various kinds of electronic crimes,

mechanisms for investigation, prosecution and adjudication in relation to

electronic crimes. Under Section 22, punishment of up to seven years or fine up

to 5 million rupees or both has been prescribed for the offence of producing,

distributing or transmitting pornographic material showing underage girls

engaged in sexually explicit conduct.

Comments

Post a Comment